Tequila's Pre-Columbian Origins

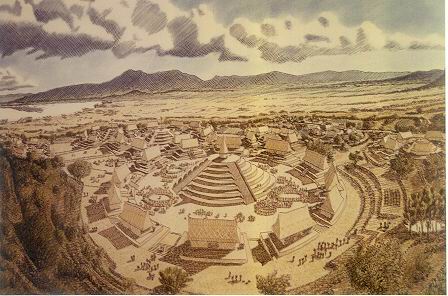

The valleys that lie

beside the volcano at the heart of the Tequila region were the home of

the a complex society that reached its peak between 200 BCE and 350 CE.

Archeologists estimate more than 50,000 people may have lived within 15

miles of the Tequila volcano. Known today as the Teuchitlán tradition

(named for the nearby town), this society was the cultural center of

West Mexico, with unique, complex architecture and a trade network that

stretched from Guatemala to Arizona.

The valleys that lie

beside the volcano at the heart of the Tequila region were the home of

the a complex society that reached its peak between 200 BCE and 350 CE.

Archeologists estimate more than 50,000 people may have lived within 15

miles of the Tequila volcano. Known today as the Teuchitlán tradition

(named for the nearby town), this society was the cultural center of

West Mexico, with unique, complex architecture and a trade network that

stretched from Guatemala to Arizona.

The Teuchitlan culture was already in decline and being replaced by

the El Grillo phase when the area was

subject to migrations of outsiders (possibly originating in nearby

Guanajuato) began to enter the area in the Epiclassic (550-900 CE). These newcomers were seem to have adopted the

Nahua* language, which was probably present in the Basin of Mexico.

Many Pre-Columbian people in Mesoamerica cultivated the agave.

Domestic agaves included (popular names in parentheses): Agave

zapota (sapodilla), Agave atrovirens (maguey), Agave fourcroydes

(henequen), Agave latissima (maguey). Agave mapisaga (maguey). Agave

sisalana (sisal) and Agave tequilana (tequil maguey).

Agave nectar was known and widely used among the Pre-Columbian

cultures. Along with honey, it was used a flavouring for several dishes,

and as a sweetener when drinking chocolate. Both were highly valued and

traded extensively throughout Mesoamerica. These products augmented

other Mesoamerican foodstuffs: maize and posolli gruels and their atolli

and pinolli drinks. There is evidence that sweetmeat dessert-like

substances made with toasted squash seeds or popped amaranth seeds and

boiled agave syrup or honey were made and given as gifts and used as

ritual offerings.

Agave nectar was known and widely used among the Pre-Columbian

cultures. Along with honey, it was used a flavouring for several dishes,

and as a sweetener when drinking chocolate. Both were highly valued and

traded extensively throughout Mesoamerica. These products augmented

other Mesoamerican foodstuffs: maize and posolli gruels and their atolli

and pinolli drinks. There is evidence that sweetmeat dessert-like

substances made with toasted squash seeds or popped amaranth seeds and

boiled agave syrup or honey were made and given as gifts and used as

ritual offerings.

Mildly alcoholic (fermented) drinks called aguamil, pulque and balche

were made using agave syrup and/or honey.

Salud! To Mayahuel, the Aztec goddess who bore 400

gods, provided sustenance to Mexico’s people and from her bosom oozed

the first alcoholic drink of the Americas. Known as pulque, this 2000

year-old, white, foamy, viscous beverage of four to eight percent

alcohol, is the mother of mezcal and the abuelita of tequila, Mexico’s

national drink.

Rachel Barron,

El Andar magazine, 2000

Agave nectar (aguamiel) is harvested primarily in Southern Mexico

from the agave varietal maguey shawii and from other members of the

agave family, most related to the Blue Agave and other maguey species

from which mezcal and sotal are made. However, there is a big difference

in the harvesting process to obtain agave nectar as opposed to the

production of tequila.

Agave nectar (aguamiel) is harvested primarily in Southern Mexico

from the agave varietal maguey shawii and from other members of the

agave family, most related to the Blue Agave and other maguey species

from which mezcal and sotal are made. However, there is a big difference

in the harvesting process to obtain agave nectar as opposed to the

production of tequila.

Agave nectar is usually sustainably harvested from the plant through a

process which extends it’s life for about three years. Just before the

agave grows its quiote, the top section of the piña is cut and scooped

out into a hollow. The agave juice collects in this hollow is harvested

daily. The nectar is then allowed to go through a natural enzymatic

process, similar to honey, which results in a sweeter and thicker agave

juice, somewhat sweeter than honey but with a thinner consistency. It

has an additional advantage: it does not crystalize like honey or maple

syrup.

Agave syrup is also quite low on the glycemic index, lower than honey,

and the fructose releases its sugars slowly, so they do not raise

the blood sugar. Agave nectar does not induce the pancreas to produce or

release insulin. This makes agave nectar a great natural sweetener for

anyone concerned about their sugar intake.

Agave syrup is also quite low on the glycemic index, lower than honey,

and the fructose releases its sugars slowly, so they do not raise

the blood sugar. Agave nectar does not induce the pancreas to produce or

release insulin. This makes agave nectar a great natural sweetener for

anyone concerned about their sugar intake.

Agave syrup was also taken to make a low-alcohol, fermented drink

called pulque. This appears to have been done for millennia,

and was a widespread practice. Maya codices depict feasting and drinking

what was probably a form of pulque. Aztec codices also show scenes with

pots brimming over, signifying the fermentation process. These are often

shown with depictions of rabbits, symbolizing fertility and plenty.

Pulque appears in pre-Hispanic "history" about 1000 A.D. A joyous

mural called the "Pulque Drinkers" was unearthed in 1968 during

excavations at the Great Pyramid in Cholula, Puebla, 70 miles east of

Mexico City.

From many graphic indications, it is obvious that pulque was not a new

thing when the mural was painted; the drink is at least 2,000 years old.

It is the sap, called aguamiel or honey water, that becomes pulque

through a natural fermentation process which can occur within the plant,

but usually takes place at a "Tinacal" (place of production).

The beverage became such an important element socially, economically

and, as a consequence, religiously, that myths, legends and cults

proliferated around it and its source, the maguey, many of which

continue today.

The beverage became such an important element socially, economically

and, as a consequence, religiously, that myths, legends and cults

proliferated around it and its source, the maguey, many of which

continue today.

In the great Indian civilizations of the central

highlands, pulque was

served as a ritual intoxicant for priests-to increase their enthusiasm,

for sacrificial victims-to ease their passing, and as a medicinal drink.

pulque was also served as a liquor reserved to celebrate the feats of

the brave and the wise, and was even considered to be an acceptable

substitute for blood in some propitiatory ceremonies.

Today the giant pulque maguey (the most common being the San Francisco

Tlaculapan) are first processed after 12 years of growth. Often an

outstanding plant will have an initiation attended by the local governor

in honor of a potentially long production cycle. A good plant can

produce for up to 1 year. The center of the maguey is regularly scraped

out activating the plants production of aguamiel. A local custom for a

man without sons is to process 6 plants, make and drink a special pulque,

and then make sons. The drink is often considered a mythic aphrodisiac.

The name Tlyaol is given to a good strain that makes one particularly

virile. Pulque is frequently the potion of choice used by women during

menstruation and lactation.

Another

use for agave seldom recognized is as a musical instrument. According to

the

Virtual Analysis of Mayan Trumpets, the Mayans and other indigenous

people used the hollowed quiote of large agave to create an instrument

that appears similar to a didgeridoo. And the

Shakuhachi Society of B.C. is doing just that: making didgeridoos

from agave quiotes (from American agave). So there is a reason to let

them grow naturally, although the market for such instruments is small.

Another

use for agave seldom recognized is as a musical instrument. According to

the

Virtual Analysis of Mayan Trumpets, the Mayans and other indigenous

people used the hollowed quiote of large agave to create an instrument

that appears similar to a didgeridoo. And the

Shakuhachi Society of B.C. is doing just that: making didgeridoos

from agave quiotes (from American agave). So there is a reason to let

them grow naturally, although the market for such instruments is small.

*"Nahuatl" is generally used for the set of

dialects that descended from Proto-Nahua, a.k.a. Proto-Aztecan "Nahua"

refers to speakers of Nahuatl, both as a noun and an adjective. "Aztec"

is a more recent word of uncertain origin, that refers to the Late

Post-classic (1000-1500 CE) Colhua Mexica, their empire, and/or their

entire cultural setting.

Sources

Back to top