Henry Hudson

1570(?) -1611(?)

Henry Hudson's Third Voyage

1609:

The New World

Last updated:

January 19, 2007

| Written &

researched by Ian Chadwick, Text & design copyright Ian Chadwick © 1992-2007 |

|

|

Web design, Net training, writing, editing, freelance columns, editorial commentary, research & data analysis. |

There have been suggestions that Hudson acted as a spy for England, using his contract to get Dutch maps for areas where the English had none. Hudson met with three Dutch cartographers during his negotiations with the United Dutch East India Company, and likely got from them maps that showed parts of the area he planned to explore on his next voyage. There is no other good explanation why Hudson broke his contract and turned away from his voyage north to sail across the ocean and explore the coast of the New World.

Unable

to find anyone in England to back his proposed expedition, Henry Hudson turned to

the Dutch - England's greatest trading rival - and was eventually hired to seek

a Northeast Passage - the direction he had taken in his unsuccessful second

voyage over the top of Russia. But after a short journey north, Hudson again faced a possible mutiny

from his crew, possibly led by Robert Juet. He turned his ship, the

Half Moon,

around and - ignoring his contract terms - instead headed for the New World

and warmer climate. Click image for a map of this voyage.

Unable

to find anyone in England to back his proposed expedition, Henry Hudson turned to

the Dutch - England's greatest trading rival - and was eventually hired to seek

a Northeast Passage - the direction he had taken in his unsuccessful second

voyage over the top of Russia. But after a short journey north, Hudson again faced a possible mutiny

from his crew, possibly led by Robert Juet. He turned his ship, the

Half Moon,

around and - ignoring his contract terms - instead headed for the New World

and warmer climate. Click image for a map of this voyage.

Hudson explored the northeastern coast of America, eventually sailing into the mouth of a wide river near today's New York City. He hoped the river - now named the Hudson River - would provide a passage west to the Pacific. But after 150 miles (240 km) - and reaching a location near where Albany sits today - he found the river had become too shallow to continue. Hudson had to turn around and head home, again proving unsuccessful at finding a way to the Orient.

The primary record of the voyage - and the only surviving English record - is the journal of Robert Juet, who had sailed with Hudson previously as mate, and would again in 1610. He noted numerous fights with the natives, killing, drunkenness, looting and even a kidnapping. The crew was generally negative towards native Americans, and somewhat afraid of them, which may have influenced later relations between native groups and European settlers. It was hardly a "glorious" expedition in terms of future diplomacy. The real importance of this voyage was in the explorations and its influence would come later, when the Dutch settled around today's Manhattan Island and founded their New World colony. Hudson's third voyage was the first to record the European discovery of today's New York State.

There is considerable contention among historians and geographers as to which landmarks Juet identified. Dr. George Asher, whose 1860 work on Hudson remains among the most important, tried to determine modern settings from Juet's record, but many of his choices were later challenged by Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes in The Iconography of Manhattan Island and other interpreters.

On his return, Hudson stopped in England, where he was arrested for sailing under another nation's flag, considered treason at the time. He and his crew stayed in England while the Dutch ship and the Dutch sailors in the crew went home, apparently with Hudson's record of the voyage.

Hudson's own log and journal went with the Half Moon back to Amsterdam, and was not seen by English eyes again. However, parts of it were quoted and reproduced in Dutch books in 1625 (see my list of sources). Only fragments of Hudson's own journal were ever reprinted. The originals were sold at auction in the early 19th century and subsequently vanished.

There have been suggestions that Hudson acted as a spy for England, using his contract to get Dutch maps for areas where the English had none. Hudson met with three Dutch cartographers during his negotiations with the United Dutch East India Company, and likely got from them maps that showed parts of the area he planned to explore on his next voyage. There is no other good explanation why Hudson broke his contract and turned away from his voyage north to sail across the ocean and explore the coast of the New World. Nor is there a good reason he sailed into England on his way home, instead of continuing to nearby Amsterdam where his employers were. Hudson was soon released from his 'arrest' to command the Discovery for his final voyage.

Or perhaps Hudson was on a mission from the English trading companies to derail or sabotage the Dutch efforts to find a shorter passage to the rich spice islands. Certainly the rivalry between the two nations was at its peak and Hudson was a product of the aggressive Muscovy Company, a direct competitor to the Dutch. England had been an ally of the Netherlands since 1577, and had sent aid and military units to help them fight the Spanish in 1584. But the Dutch were aggressive and active traders and their interests conflicted with the goals of the English. By 1600 the Dutch were the supreme European trading power in the Indonesian archipelago, displacing the Portuguese who had held a monopoly for much of the 16th century.

In 1591 Dutchman William Usselinx returned and began to agitate among his countrymen for increased trade with the New World. He kept arousing public opinion until his death at 80, leaving behind 50 printed works. He was also responsible for the founding of the Dutch West India Company, in 1621. Before then, the States-General offered a prize of 25,000 guilders to anyone who discovered a Northeast Passage to China and Japan. That reward may have lured Hudson to Amsterdam.

Dutch merchantmen had already navigated the St Lawrence river in 1607. But the most naval event of the year was the battle of the Bay of Gibraltar. The Dutch States-General sent 26 small vessels to the Spanish coast where the Dutch admiral saw an opportunity to challenge the Spanish war fleet, then in the Bay of Gibraltar. Heemskerk attacked the Spaniards on April 25th. Both the admirals were slain, but the Spanish fleet was totally destroyed; the crews and the soldiers were put to the sword. This convinced Spain that the 40-year-old war with the Dutch would not end with victory any time soon. it also made Spanish reconquest of the Spice Islands and the forcible extinction of the Dutch East India Company seem remote. The restoration of Spanish influence in the Indian seas never came about.

Dutch merchants, denied trade with France and Spain because of the state of war, aggressively sought new markets in Italy, Russia, Turkey and the Orient.

The year 1609 saw the beginning of a cease-fire in the Dutch war for independence, which had been raging since 1548. Called the Twelve Years' Truce, it temporarily ended hostilities between the United Provinces and the southern states. The truce was mediated by France and England at The Hague. This allowed the Dutch to turn their energies to trade and consolidating their hold on the spice trade. The head of the United Dutch East India Company (VOC) at this time was the ruthless Jan Pieterzoon Coen. Coen destroyed plantations in Indonesia so he could raise the prices of spices like nutmeg and clove artificially high, destroying the livelihood of much of the island populations in the process.

Amsterdam had become the trading capital of Europe by 1600. It had eclipsed Antwerp when the latter was captured by the Duke of Parma in 1585 and by 1622 was one of the wealthiest - if not the wealthiest - city in Europe. Her population tripled between 1585 and 1622 to more than 100,000 people, and her port was dense in ships, her warehouses full of merchandise.

In 1609, the Bank of Amsterdam was founded. Before the end of the century the bank had deposits worth $180,000,000, a treasure more prodigious than any European financier at that time thought could be possibly accumulated.

1608

After his second failure to find a passage, no English

company was interested in Hudson's continued quest. Hudson was miserable with his

failure. Rev. Samuel Purchas wrote he met with Hudson in the fall and found

the explorer "sunk into the lowest depths of the Humour of Melancholy,

from which no man could rouse him. It mattered not that his Perseverance and

Industry had made England the richer by his maps of the North. I told him

he had created Fame that would endure for all time, but he would not listen

to me."

After his second failure to find a passage, no English

company was interested in Hudson's continued quest. Hudson was miserable with his

failure. Rev. Samuel Purchas wrote he met with Hudson in the fall and found

the explorer "sunk into the lowest depths of the Humour of Melancholy,

from which no man could rouse him. It mattered not that his Perseverance and

Industry had made England the richer by his maps of the North. I told him

he had created Fame that would endure for all time, but he would not listen

to me." - Sometime in the autumn, Hudson was visited by Emmanuel van Meteran (Emanuel van Meteren), former Dutch Consul in London and English representative of the Dutch East India Company. He also invited Hudson to dinner at the Dutch Consulate. van Meteren may have persuaded Hudson to enlist in the service of the Dutch East India Company. van Meteren would have been aware that the Dutch States-General had posted an offer of reward of 25,000 guilders to anyone who could discover a northeastern route to China and Japan - through the Arctic waters north of Russia.

- September: (?) Hudson attended the christening of his granddaughter, Alice (Oliver's daughter), at the church of St. Mary Aldermary, in London.

- November: The Consul presented Hudson with a letter indicating the directors of the Dutch East India Company would like to meet him and would pay his expenses to get to Holland. The Company, which had a monopoly on trade with the Orient, wanted to shorten the lengthy and expensive voyage around the Cape of Good Hope to the source of the spices.

- At first, the 17 Company directors were impressed by Hudson, but a few were skeptical that he could find a passage through the northern route. It had been more than 12 years since a Dutch vessel attempted to find a passage through the northeast. The powerful director de Moucheron wrote "Master Hudson's plans are not a good investment for the Dutch East India Company." The skeptics managed to get the others to agree to hold a full meeting of the board on March 25 to vote on the issue, but that would be too late for Hudson to outfit a ship. So they paid Hudson for his trip to Amsterdam and dismissed him.

- Hudson turned to Dutch geographer Peter Plancius, and convinced him a passage could be found to the northwest. Plancius favoured the northeast route as more likely and they debated the merits of both many times, in the process becoming close friends. Hudson drew freehand maps of his voyages for Plancius to keep.

- In Holland, Hudson also met with Jodocus Hondius, an engraver. Hudson helped Hondius create his famous map of the Far North. Hudson stayed at Hondius's home in The Hague. According to Chamberlain, Hondius may have warned Hudson that there was no passage to the northwest because a relative had explored the bay and found no exit.

- King Henry IV (Henry of Navarre) of France met with James Lemaire, a Dutch navigator who was residing in Paris. Lemaire apparently knew Hudson and told Henry he was the best man to lead France's northern voyages.

- Pierre Jeannin, French ambassador, was instructed by King Henry IV to meet with Hudson in a secret interview. Hudson told him his needs, and in January Jeannin reported back to his king in a letter, recommending France should hire Hudson to search for a northwest passage. He wrote, "With regard to the northern passage, your majesty might undertake the search openly, and in your majesty's name, as a glorious enterprise."

- December 29: When they learned of Hudson's meeting with their rivals, the French, the Dutch Company directors relented before the French could make an offer. They decided to hire Hudson to look for a northern passage, but only along the way of his last voyage (northeast).

- The DEIC sent Hudson a letter in The Hague, and requested him to return to Amsterdam. Hudson replied he would do so after he celebrated the New Year.

1609

- January 8: Hudson (assisted by Jodocus Hondius as interpreter and witness) and the Dutch United East India Company signed a contract for Hudson to search for a northeast passage. He would receive 800 guilders for leading the expedition; his wife would get an additional 200 guilders, plus more, if he failed to return in a year. The Company also agreed to pay the expenses of his family living in Amsterdam, during his absence, and stipulated they had to live in Holland without working for anyone but the Dutch East India Company. It is unlikely, however, that Hudson intended to fulfill the terms of the contract.

- The contract was quite specific as to where Hudson was meant to explore, and stipulated, "the above named Hudson shall, about the first of April, sail in order to search for a passage by the north, around the north side of Nova Zembla, and shall continue thus along that parallel until he shall be able to sail southward to the latitude of sixty degrees. He shall obtain as much knowledge of the lands as can be done without any considerable loss of time, and if it is possible return immediately in order to make a faithful report and relation of his voyage to the Directors, and to deliver over his journals, log-books, and charts, together with an account of everything whatsoever which shall happen to him during the voyage without keeping anything back."

- In order to further bind Hudson, the contract stated his wife and children were required to live in Holland, where they would be under the watchful eye of the company and its agents. "It is stipulated and agreed with the before named Hudson that he shall make his residence in this country with his wife and children..."

- Only two of the 17 directors signed the contract, which may have been done to excuse the Company of legal liability later, should Hudson fail. Or it may have been done simply to prevent Hudson from entering another employ.

- Hudson spent the next three months outfitting the ship and working out possible routes with Plancius. Since neither spoke the other's language, they conversed in Latin, an indication Hudson had some higher education.

- During this time, Hudson received a letter and a set of maps from his friend Captain John Smith, of the English settlement of Jamestown in the colony of Virginia. Smith had heard the Indians tell of a river - possibly a sea - that opened to the west, possibly to the north in Canada, but he didn't have the resources to explore it. Both Hudson and Plancius were intrigued. Plancius gave Hudson George Weymouth's journal of his 1602 voyage, which had taken him 300 miles (100 leagues) into what Davis called the 'Furious Overfall.'

- Possibly sensing Hudson's potential duplicity, just before he sailed, the DEI Company amended the contract to define Hudson's goal: "To think of discovering no other route or passage, except the route around the north or northeast above Nova Zembla."

- It had been seven months since Hudson's last voyage. He had in his possession a translation of a book written in 1560 by Greenlander Iver Boty, later reprinted by Purchas in 1625. Richard Hakluyt also translated and published the travels of Ferdinand de Soto in 1609.

- Hudson signed Robert Juet on again, this time as one of the mates (another was Dutch, as was the b'o'sun). Juet's journal survived and was published in 1625, although it has several significant gaps in it. Juet also kept a journal on this trip, suggesting he was also literate and he understood navigation.

- Hudson's son John was aboard again, on the manifest this time as a passenger. John Coleman (Colman), mate on Hudson's first voyage, was also part of the crew, as second mate.

- There was a crew of 20 selected for the journey, a mix of English and Dutch sailors, most of whom did not speak the other's language. Hudson himself did not speak Dutch. The Dutch crew were more used to sailing temperate and warm waters (many had sailed in the East Indies the previous year). In a letter to his wife before the voyage, Coleman wrote of the Dutch sailors, "I hope that these square-faced men know the sea. Looking at their fat bellies, I fear they think more highly of eating than of sailing." Also critical of the Dutch, Juet wrote, "They are an ugly lot."

- Some records show the crew at only 16 members. Twenty would be a large number for such a small ship.

- The director of the DEIC, Dirk Van Os, balked at paying Hudson's high crew wages, but

the contract was ambiguous as to who had the authority to hire and set wages, so the

directors capitulated. Director Isaac Le Maire, who had supported Hudson, wrote to Van Os,

asking, "If he rebels here, under our eyes, what will he do when he is fairly away

from us?"

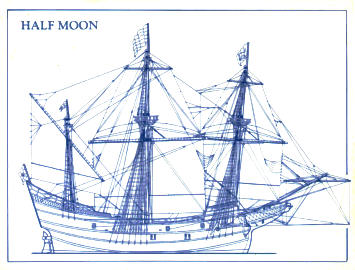

- Juet would later claim the directors decided that, since Hudson exceeded their budget, they would only give him an old, inferior ship rather than a new one. The ship they selected was the Half Moon, a cramped, ungainly 60-80 ton ship that rode high in the water. La Maire, who complained of the choice, wrote "she will prove difficult to handle in foul weather." When Hudson tried to get another ship, the Van Os wrote to him "The Half Moon is the only ship at the disposal of the Dutch East India Company... We can give you no other ship. If you do not want the Half Moon, the Company will be obliged to find another Captain to carry out this assignment."

- The Half Moon was named after the victorious flagship in which Vice-Admiral Kant had beaten the Spaniards in a great naval battle in 1602.

- Hudson received a retainer from the directors for a second voyage under the Dutch flag, supposed to take place in 1610.

- March: The directors wrote to Hudson, instructing him to sail "no later than the fifteenth day of March." But yet Hudson delayed.

April

-

6: The ship Half Moon

(Halve Maen in Dutch) was commissioned for the Dutch East India Company and set

sail, with a second Dutch ship following - possibly the "Good Hope".

(Some accounts suggest the date was April 1).

6: The ship Half Moon

(Halve Maen in Dutch) was commissioned for the Dutch East India Company and set

sail, with a second Dutch ship following - possibly the "Good Hope".

(Some accounts suggest the date was April 1).

- The Half Moon was one of the speedy type of vessels built for the difficult navigation of the Vlie and Texel. They were known as "Vlie-boats,' fast sailing yachts called "fly-boats" by the English. Usually, they were of about 50 lasts (100 tons) burden, but the Half Moon was only 40 lasts (80 tons).

- Since Hudson's logs were returned to Holland with the ship after its return, the full identity of the crew is not fully known. A few fragments from Hudson's logs were published in Amsterdam in 1625. The main record comes from Juet's own journal, published in England in 1625. Juet started his journal using the Julian calendar (March 25 by 'the old account') but quickly switched to the Gregorian calendar ('stilo novo' - new style) for May 5. England did not officially accept the Gregorian calendar until 1752, at which point the 'new' calendar added 14 days to the Julian date.

- Samuel Purchas opens Juet's account with, "The third Voyage of Master Henrie Hudson toward Nova Zernbla, and at his returne, his passing from Farre llands, to New-found Land, and along to fortie foure degrees and ten minutes, and thence to Cape Cod, and so to thirtie three degrees; and along the Coast to the Northward, to fortie two degrees and a. haÏf, and up the River neere to fortie three degrees. Written by Robert Juet of Lime-house."

- 8: Two days after they set sail, Half Moon cleared the island of Texel, and left all Dutch land behind. Hondius wrote to Plancius on this day, saying, "I have heard that Hudson began his adventure two days ago." Obviously Hudson's friends were not at the dock when he left, so the start may have been inauspicious, and lacking any of the usual ceremony and religious service that preceded voyages.

May

- 5: Thirty miles off the North Cape (Norway), Hudson directed his course back toward the islands of Nova Zembla ("Novaya Zemlya"). Juet wrote, "On Saturday the five and twentieth of March, 1609 after the old Account, we set sayle from Amsterdam; and by the seven and twentieth day we were downe at the Texel: and by twelve of the clocke we were off the Land, it being East of us two leagues off. And because it is a journey usually knowne, I omit to put downe what passed, till we came to the height of The North Cape of Finmarke, which we did performe by the fifth of May (stilo novo) being Tuesday. On which day we observed the height of the Pole, and found it to be 71 degrees and 46 minutes; and found our Compasse to vary six degrees to the West: and at twelve of the clocke, the North Cape did beare South-west and by South, ten leagues off, and wee steered away East and by South, and East."

- Mid-late May: The ship was blocked by bad weather and icy waters along the north coast of Europe, near Norway. The crew was quarrelsome and fights broke out often between English and Dutch sailors.

- After contending for more than a fortnight with head winds, continual fogs, and ice, Hudson found it impossible to reach even the coast of Nova Zemlya, where he had been the year before. The crew was cold and quarrelsome.

Another

mutiny or outbreak of the crew, possibly led by Juet, broke out. It may also

have been led by

the Dutch who were not used to sailing in the cold, stormy Arctic waters and wanted to turn

around.

Another

mutiny or outbreak of the crew, possibly led by Juet, broke out. It may also

have been led by

the Dutch who were not used to sailing in the cold, stormy Arctic waters and wanted to turn

around. - Hudson decided to change course and go to the New World. He showed the crew the maps of John Smith and the crew agreed to head west towards North America for warmer sailing. He offered the crew a choice: sail west looking for the Indies by way of a sea that Capt. John Smith told Hudson was just north of the English colony in Virginia, or to search for a more northerly passage via Davis' Strait.

- Van Meteren described it thus, "This circumstance, and the cold, which some of his men, who had been in the East Indies, could not bear, caused quarrels among the crew, they being partly English, partly Dutch, upon which Captain Hutson laid before them two propositions. The first of these was to go to the coast of America, to the latitude of 40 degrees, moved thereto mostly by letters and maps which a certain Captain Smith had sent him from Virginia, and by which he indicated to him a sea leading into the western ocean, by the north of the southern English colony."

- Hudson then turned back west, heading across Atlantic. He probably planned to look for a northwest passage all along, and may have told some of the crew this when they rebelled. During this time, Hudson may have sent the second Dutch ship home. It is not noted in Juet's journal, but an account was provided in Historie der Nederlanden by Emanuel van Meteren, 1614.

- 19: The Half Moon doubled the North Cape again, and in a few days saw a part of the western coast of Norway, in the latitude of 68 degrees. A violent snowy storm blew them west for a few days, about 200 miles. From this point Hudson sailed for the Faeroe Islands, where he wanted to get fresh water and supplies.

- 19: During stormy weather, Juet reported the sun "having a slake," which

some writers suggest meant he saw a sunspot. However, this is unlikely without a telescope

(a working telescope was not even made until 1609, when Galileo built the first one), and

he probably meant a 'slackening' or lowering of intensity due to cloud cover. The first

sunspot would not be reported until 1610, when Thomas Hariot recorded one on December 8.

- 26: Another violent storm, the worst of the voyage, rocked the ship.

- 29: Stopped at the Faeroe Islands for water. Hudson bartered with local natives for food.

June

- 2: Juet wrote the Half Moon sailed southwest to look for Busse (Buss) Island, supposedly discovered in 1578, at around 57 degrees N, by one of Frobisher's ships (The Emmanuel, known as the "Busse of Bridgewater"). But they never found it - nor did anyone else. The island was never seen again and may have been a mirage, a myth or even a mistaken reading of the ship's position.

- 3: The sailors were surprised at the force of the current, today known as the Gulf Stream.

- 15: More storms beset the ship on her western passage. Her foremast was swept overboard and her deck damaged.

- 19: A temporary mast and foresail were erected during a calm.

- 25: The crew spotted another ship and attempted to catch her, chasing her most of the day, probably hoping to capture her for booty. But the other ship managed to outrun the clumsy Half Moon.

- 27: Another storm forced the ship south.

July

- 2: The Half Moon sounded the Grand Banks off Newfoundland.

- 3: They moved south, where they spotted a fleet of French fishing vessels, but didn't speak with them. The crew took soundings and caught 100-200 cod.

- 8: The Half Moon reached Newfoundland and sails west-southwest.

- 12: Hudson sighted the coast of North America, a "low white sandie ground,"

- 13: Off Cape Sable, Nova Scotia.

- 14: Off Penobscot Bay, Maine. For three days the ship was trapped in a deep fog, which lifts on the fourth day. The crew was able to go ashore where they met and trade with natives who offered them no harm.

- 17: The crew went ashore again to trade and meet the natives.

- 18: Anchor in George's Harbour. Hudson went ashore, his first landing in the New World.

- 19: Crew traded with natives. Juet wrote: "The people coming aboard showed us great friendship, but we could not trust them." He remained suspicious of the natives, despite no effort to do them harm. The crew continued to trade with the natives for several days while they remained at anchor, fixing their mast. They caught and cooked 31 lobster. Hudson ate with his men at this feast, providing two jugs of wine from his private stores.

- 21-22: The crew cut several spare masts and stores them in the hold. On July 21, the ship's cat went crazy, upsetting the superstitious crew. It "ran crying from one side of the ship to the other, looking overboard. This made us wonder, but we saw nothing."

- 24: Juet wrote: "We kept a good watch for fear of being betrayed by the people, and noticed where they kept their shallops." The crew catch 20 "great cods and a great halibut" in nearby waters.

- 25: Juet took an armed crew of six men to the native village and wrote in his journal "In the morning we manned our scute with four muskets and six men, and took one of their shallops and brought it aboard. Then we manned our boat and scute with twelve men and muskets, and two stone pieces, or murderers, and drave the salvages from their houses, and took the spoil of them, as they would have done us."

- The crew stole a boat that morning, then later in the evening, 12 armed crew went back and drove the Indians away from their encampment, stealing everything they could, on the pretense the natives would have done the same to them. No one was punished for this act.

- 26: Fearful of an Indian counterattack, Hudson sailed away at 5 a.m.

August

- 3: Hudson passed Cape Cod which he named "New Holland," until he realized it is the land discovered by Capt. Gosnold in 1602. He sailed on and discovered Delaware Bay. The crew went ashore again. Inexplicable events such as the self-destruction of the native boat being towed behind the ship convinced the superstitious crew that the voyage was doomed to failure. The men became surly and angry again.

- 4: The crew went ashore to trade with the "savages" (you can read Juet's journal at www.lihistory.com/vault/hs216a1v.htm).

- Mid-August: After fair, hot weather for weeks, the Half Moon sailed south, not far from Jamestown, but Hudson made no effort to visit his friend, John Smith. Hudson was probably aware that Dutch explorers upon this coast would be regarded by Englishmen as poachers.

- 18: Amid gusts of wind and rain, Half Moon was off the Accomac peninsula and sighted an opening, probably Machipongo Inlet, which Hudson mistook for the James River.

- 19: The Half Moon headed north again, hugging the shoreline.

- 21: A severe storm tore the sails, but no other damage was recorded.

- 28: The lookout reported sighting a large bay, (Delaware Bay). Hudson tried to navigate it, and sailed about nine miles, but it became too shallow and full of shoals. He found many shoals, and several times the Half-Moon was struck upon the sands; the current, moreover, set outward with such force as to assure him that he was at the mouth of a large and rapid river. This was not encouraging. After a day, he gave up, went back and headed north again.

September

- 2: The lookout saw a "great fire" ashore on the highlands of Navesink. Hudson anchored near what is now Sandy Hook.

- 3: He lifted anchor and sailed into the bay, passing Staten and Coney Islands by 3 p.m. He reached the mouth of a wide river (now Hudson River) and decided to sail up it, hoping it will widen into a passage. This river had been noted before by earlier explorers and was indicated on French maps sent to Hudson earlier by Capt. John Smith as the "Grande River."

- An Italian, Giovanni da Verranzano, was the first recorded European to discover the mouth of the river when he was sailing for the French in 1524. He wrote, "We found a very pleasant situation amongst some steep hills ... ," but did not continue exploring what he called, "The River of the Steep Hills" and the "Grand River." A Portuguese explorer, Estevan Gomez, also arrived at the mouth of the river a few months later in 1524. Gomez called it the Rio de San Antonio.

- Hudson claimed the area along the river for the Dutch, who had employed him, and opened the land for settlers who would follow. His voyage came 10 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock.

- 4:Natives greeted Hudson and give him his first taste of American corn, which Hudson called 'Turkish wheat.'

- 5: Most of the crew went ashore. Natives gave Hudson gifts of tobacco. Hudson gave

them knives and beads in return. He wrote they were "very civil" but Juet

wasn't convinced they were friendly. He wrote:

"Our men went on Land there, and saw great store of Men, Women and Children, who gave them Tabacco at their coming on Land. So they went up into the Woods, and saw great store of goodly Oakes and some Currants. For one of them came aboord and brought some dryed, and gave me some, which were sweet and good. This day many of the people came aboord, some in Mantles of Feathers, and some in Skinnes of divers sorts of good Furres. Some women also came to us with Hempe. They had red Copper Tabacco pipes, and other things of Copper they did weare about their neckes. At night they went on Land againe, so wee rode very quiet, but durst not trust them."

- 6: Hudson sent John Colman (Coleman) and four others to sound another river, about 12 miles away. During the exploration along the journey north, some of the crew were assaulted by natives in two canoes; one contained twelve and the other fourteen. Colman, who had accompanied Hudson on his first voyage, was killed by an arrow shot into his throat, and two more were seriously wounded.

- 7: The dead were buried ashore the next day at a place they named Colman's Point. The ship remained at anchor that night "keeping a careful watch."

- 8: Traded with natives onboard Half Moon again. Juet recorded they kept a careful watch to "see if they would show any sign of the death of our man, which they did not."

- 9: Two "great canoes" full of natives came on board. Juet wrote: "in an attempt to deceive us, pretended interest in buying knives. But we were aware of their intent and took two of them prisoners" as insurance against further attack. The natives were dressed in red coats from the crew's wardrobes.

- According to Vail, Hudson wrote, "Had they indicated by a cunning light in their eyes that they had knowledge of the foul murder (of Sept. 6), I was prepared to order my company to exterminate all without delay." Another pair of natives was grabbed later, one was held captive, and the other released. But the second one jumped overboard and escaped.

- Kidnapping natives was a common practice for European explorers. For example, in the 1560s, an Inuit mother and child were kidnapped by the French and taken back to Europe where they were put on display. People could pay to gawk at them. In 1576 Martin Frobisher returned to England with an Inuit he had kidnapped. The Inuit man soon sickened and died. In 1524, Giovanni da Verrazano's crew kidnapped an Algonquian child, but were unsuccessful in their attempt to kidnap a native woman. In 1525, Estban Gomez kidnapped Native Americans as slaves. On his second trip to America, 1525, Jacques Cartier kidnapped his host, Chief Donnacona, and nine other Indians, who were taken to France where they all died. Squanto, the interpreter for the Plymouth Colony, was captured along with 27 other natives, by Capt. Thomas Hunt in 1614 and taken to Europe where they were sold as a slave. In 1605, Captain George Weymouth kidnapped five Indians from the New England coastline.

- 10: Hudson set sail and heads up the river.

- 11: Hudson sailed through the Narrows and anchored in New York Bay. The first night he anchored off the northern tip of Manhattan.

- 12: A flotilla of 28 canoes, filled with men, women and children approached, but, Juet wrote, "we saw the intent of their treachery and would not allow any of them to come aboard." However, the crew bought food from them. Hudson noted the natives used copper in their pipes and inferred there was a natural source nearby.

- 13: The crew traded for oysters with the Native Americans; the ship was near today's Yonkers.

- 14: Hudson thought he may have found the long-sought passage when he saw the wide Tappan Zee, but when he reached the shallower area near Albany, he realized his mistake. Juet wrote, "the 14th, in the morning, being very fair weather, the wind southeast, we sailed up the river 12 leagues ... The river is full of fish."

- 15: Two captive natives escaped and swam ashore where they taunted the crew. At night the crew found another native village with "a very loving people and very old men and we were well taken care of."

- 17: The Half Moon ran aground, but was soon pulled free.

- 18: Hudson accepted an invitation from a chief to eat with him and went ashore. The natives "killed a fat dog and skinned it in great haste" for dinner. Hudson was invited to stay overnight, but was suspicious. Sensing his discomfort, the natives broke their arrows and threw them into the fire to indicate their good intentions. But Hudson returned to the ship anyway. He wrote, "The land is the finest for cultivation that I ever in my life set foot upon."

-

Hudson went to a feast with the natives. He would write of this visit in

his journal: "I sailed to the shore in one of their canoes, with an old man who was the chief of a tribe consisting of 40 men and 17 women. These I saw there, in a house well constructed of oak bark, and circular in shape, so that it had the appearance of being built with an arched roof. It contained a great quantity of maize or Indian corn, and beans of the

last year's growth; and there lay near the house, for the purpose of drying, enough to load three ships, besides what was growing in the fields. On our coming into the house, two mats were spread our to sit upon, and some food was immediately served in well-made red wooden bowls. Two men were also despatched at once, with bows and arrows inquest of game, who soon brought in a pair of pigeons, which they had shot. They likewise killed afar dog and skinned it in great haste, with shells which they had got out of the water. They supposed that I would remain with them for the night; but I returned, after a short time, on board the ship. The land is the finest for cultivation that I ever in my life set foot upon, and it also abounds in trees of every description. These natives are a very good people; for when they saw that I would not remain, they supposed that I was afraid of their bows; and , taking their arrows, the broke them in pieces and threw them into the fire."

Hudson went to a feast with the natives. He would write of this visit in

his journal: "I sailed to the shore in one of their canoes, with an old man who was the chief of a tribe consisting of 40 men and 17 women. These I saw there, in a house well constructed of oak bark, and circular in shape, so that it had the appearance of being built with an arched roof. It contained a great quantity of maize or Indian corn, and beans of the

last year's growth; and there lay near the house, for the purpose of drying, enough to load three ships, besides what was growing in the fields. On our coming into the house, two mats were spread our to sit upon, and some food was immediately served in well-made red wooden bowls. Two men were also despatched at once, with bows and arrows inquest of game, who soon brought in a pair of pigeons, which they had shot. They likewise killed afar dog and skinned it in great haste, with shells which they had got out of the water. They supposed that I would remain with them for the night; but I returned, after a short time, on board the ship. The land is the finest for cultivation that I ever in my life set foot upon, and it also abounds in trees of every description. These natives are a very good people; for when they saw that I would not remain, they supposed that I was afraid of their bows; and , taking their arrows, the broke them in pieces and threw them into the fire." - Some authorities suggest Hudson landed at latitude 42° 18', five or six miles above the present city of Hudson. However, a careful computation of the distances covered each day, as entered in Juet's book, shows that on September 18 the "Half Moon" was six leagues higher up the river; the real landing probably was in the neighbourhood of today's Schodack and Castleton.

- 19: Anchored near present-day Albany, where they traded with natives. De Laet states that Hudson explored the river "to nearly 43° of north latitude, where it became so narrow and of so little depth that he found it necessary to return." As Albany is in 42° 39', the boat must therefore have gone above that place "eight or nine leagues" further as Juet wrote in his journal.

- 20: The mate and four others took the ship's boat upriver to sound for depth. They returned at night, with measurements of two fathoms about six miles further, which deepened to six and seven past that.

- 21: The crew got some natives drunk on wine and Aqua Vitae -"hooch," from the Indian word "hoochenoo" for the hard liquor Hudson and his crew plied them with. One passed out and slept aboard the ship. The natives returned the next day and were relieved to find him unharmed.

- 22: Another row boat sent out returned with the bad news: the river became shallower further ahead. They travelled about 24-27 miles and found the water only seven feet deep. After sailing 240 km (150 miles) from the mouth of the river, Hudson decided he must turn back.

- 23: Half Moon headed six miles back down river.

- 24: After wasting a day stranded on a shoal, the Half Moon got free and started down river again.

- 27: Half Moon ran aground again.

- Hudson called the river the "River of Mountains" although the Native Americans, with whom the skipper and crew met, called it "Muhheakunnuk" (great waters constantly in motion).

October

- 1: Near Peekskill, the ship stopped and crew traded with natives. One native snuck into Juet's cabin and stole some clothes and a pillow. The Dutch mate discovered the theft and shot the Indian, killing him. Another was killed by the cook as he attempted to climb aboard. The other natives jumped overboard and fled, pursued by some of the crew. The Half Moon lifted anchor and sailed six miles before stopping for the night.

- 2: Twenty miles further, as the ship neared Manhattan (the river "Manna-hata;" the name of the natives living on the island was Mannahattes), about 100 natives ambushed the Half Moon and chased it in their canoes. Both sides traded shots. Hudson ordered guns to be fired at them. Several natives were killed, and the event was remembered by the natives 15 years later when the Dutch came to settle in Manhattan in 1624.

- 4: Hudson returned to the mouth and left to return to the Old World.

- The Dutch mate suggested they winter over in Newfoundland and continue to explore for a northwest passage through Davis' Strait the next year, but the men had begun to "threaten" Hudson "savagely," if they were not taken home. So, after leaving Sandy Hook, Hudson set his course "straight across the ocean' for home.

- Van Meteren wrote, "While at sea, they held counsel together, but were of different opinions. The mate, a Dutchman, advised to winter in Newfoundland, and to search the northwestern passage of Davis throughout. This was opposed by Skipper Hutson. He was afraid of his mutinous crew, who had sometimes savagely threatened him; and he feared that during the cold season they would entirely consume their provisions, and would then be obliged to return, [with] many of the crew ill and sickly. Nobody, however, spoke of returning home to Holland, which circumstance made the captain still more suspicious. He proposed therefore to sail to Ireland, and winter there, which they all agreed to."

November

- 7: The Half Moon returned, sailing into Dartmouth (England, not Holland) after being away 7 1/2 months. Robert Juet (who may have been Hudson's clerk, since it was recorded the mate was Dutch) recorded in his journal, "by the grace of God we safely arrived in the range of Dartmouth, in Devonshire." There is no record left to say why Hudson chose to land in England, rather than continue on to Amsterdam. His ship was not damaged and there was nothing recorded to suggest supplies were running out.

- Van Meteren wrote, "At last they arrived at Dartmouth, in England, the 7th of November, whence they informed their employers, the Directors in Holland, of their voyage. They proposed to them to go out again for a search in the northwest, and that, besides the pay, and what they already had in the ship, fifteen hundred florins should be laid out for an additional supply of provisions. He [Hudson] also wanted six or seven of his crew exchanged for others, and their number raised to twenty. He would then sail from Dartmouth about the 1st of March, so as to be in the northwest towards the end of that month, and there to spend the whole of April and the first half of May in killing whales and other animals in the neighborhood of Panar Island, then to sail to the northwest, and there to pass the time till the middle of September, and then to return to Holland around the northeastern coast of Scotland. Thus this voyage ended."

- 8: Less than 24 hours after landing, Hudson wrote to the directors of the East India Company, recommending a trip to find a northwest passage could begin around March 1, 1610. However, he wanted to replace six or seven of his crew for more tractable and docile members - giving his employers only the barest hint of the problems he had faced. The letter took weeks to arrive, and while he waited, Hudson and the crew continued to live aboard the Half Moon.

- When they received Hudson's letter, the directors sent for Hudson to bring the Half Moon to Amsterdam immediately.

- Van Meteren wrote, "A long time elapsed, through contrary winds,

before the Company could be informed of the arrival of the ship in England.

Then they ordered the ship and crew to return as soon as possible. But, when

this was about to be done, Skipper Henry Hutson and the other Englishmen of

the ship were commanded by the government there not to leave [England], but

to serve their own country. Many persons thought it strange that captains

should thus be prevented from laying their accounts and reports before their

employers, having been sent out

for the benefit of navigation in general. This took place in January, [1610]; and it was thought probably that the English themselves would send ships to Virginia, to explore further the aforesaid river."

December

- Hudson, however, couldn't leave. An English Order in Council censured Hudson for 'voyaging to the detriment of his country' and forbade him to undertake any foreign service, and even forbade further correspondence with the East India Company. This was unusual, because many mariners worked for countries other than their own. Jealous English merchants may have been behind Hudson's arrest.

- In mid-December, the adventurers were escorted to London to appear before the King (James), who was apparently angry at Hudson. A guard was placed on Hudson's house and he was under a form of house arrest, kept in the district around the Tower of London..

- Hudson and the English members of his crew never returned to Amsterdam.

1609

- The Sea Venture, a ship of the Virginia Company was wrecked in the Bermudas during a hurricane on the 25th of July. It carried the interim governor of the colony onboard. News of its apparent loss was devastating to both the colony and the company in England. But all aboard survived and soon built two ships to take them to their destination. In May, 1610, they sailed into Jamestown. News of the dramatic arrival was in London’s bookstalls in October.

- Tea from China is shipped to Europe for the first time, by the Dutch East India Company.

1610

July: After an exchange of notes between England and Holland, the remaining Dutch

crew sailed the Half Moon to Holland, with Hudson's charts and logbooks. Vail says this

was in mid-December, 1609 but that was too soon for the exchange of mail in those days.

She was put back into service the following spring under the command of Laurens Reael, but

sank in 1616 or 1618. A replica was built in Holland in 1909 but was destroyed by fire in

1934. Another was built in Albany, in 1989.

July: After an exchange of notes between England and Holland, the remaining Dutch

crew sailed the Half Moon to Holland, with Hudson's charts and logbooks. Vail says this

was in mid-December, 1609 but that was too soon for the exchange of mail in those days.

She was put back into service the following spring under the command of Laurens Reael, but

sank in 1616 or 1618. A replica was built in Holland in 1909 but was destroyed by fire in

1934. Another was built in Albany, in 1989. - The Spanish Inquisition expelled the Moors from Spain in 1609-10, forcing its most educated and faithful subjects to leave, weakening Spain's future and its ability to explore and trade further.

Aftermath:

1610

- After its eight-month detention in England, the Half Moon

finally reached Amsterdam by summer, 1610. Although initially

disappointed at Hudson's failure to find the hope-for passage to the

Indies, Dutch merchants realized the area of the New World Hudson had

explored was worth further exploration and exploitation. As a result

of these discoveries, they claimed a territory that extended from

the mouth of the Delaware on the South, to Cape Cod on the

Northeast. The St. Lawrence, in Canada, was its northern frontier,

and its western boundaries were unexplored and unknown.

The Dutch immediately recognized this land could be a potential source of trade and commissioned Adriaen Block, a Dutch navigator, and fellow captain Hendrick Christiaensen to return to the area Hudson had explored. The ships brought back furs (especially in beaver pelts, which were a lucrative market in Europe) and two sons of a native chief. Hudson, of course, never returned to these lands. Block made four voyages to the area from 1611 to 1614, Christiaensen made two.

1612

- Dutch historian Hessel Gerritz wrote that many in Holland believed Hudson "purposely missed the correct route to the western passage" because he was "unwilling to benefit Holland and the directors... by such a discovery." Some historians believe Hudson was secretly working for the English, to get the information at the cost of the Dutch, but his treatment by the court on his return suggests otherwise. Hudson may have been spying on the English colony of Virginia, trying to ascertain whether there was a passageway in that area. I have reprinted some classical or out-of-print sources on my page at hudson_quotes.htm

- The Dutch East India Company, which had sent Hudson on his original voyage, decided it was worthwhile to send Block on two additional voyages to the Hudson River, aboard the Fortuyn.

1613

- Adriaen Block, sailing the Tyger accompanied by other Dutch ships, continued to explore the area discovered by Hudson in 1609. It was his fourth voyage to the lower Hudson. While moored along southern Manhattan, the Tyger caught fire and was destroyed. Block and his men, with help from the crew of the Lenape, built the 42-foot ship 16-ton Onrust (Restless).

- Block took command of the Restless and explored the East River. Block sailed up the Hudson river and wintered near Albany where he established trade with the natives in the area.

1614

- Adriaen Block returned down the river into Long Island Sound (which he may have been the first European to enter). He then sailed through the East River passage, naming it Hellegat (Hell Gate). He explored Long Island Sound and sailed up the Housatonic River (which he named "River of Red Hills"). He turned north and discovered the Connecticut River, which he entered and sailed at least as far as present day Hartford, about sixty miles. Block sailed past and named Block Island for himself, and explored Narragansett Bay.

- When Block reached Cape Cod, he rendezvoused with one of the other ships of the expedition and left the Restless behind when he returned to Amsterdam.

- Block's 1614 "Figurative Map," made after his return, showed details of the southern coast of New England and was the first to show Long Island and Manhattan as separate. He was the first explorer to name the area "New Netherland" to the area between English Virginia and French Canada.

- Block, Christiaensen, and 12 other merchants formed a new company called the United New Netherland Company. On October 11 they asked the States General for exclusive trading privileges in the area, and the company was granted exclusive rights for three years.

- Flemish (Dutch) historian Emmanuel Van Meteren's book, Historie der Nederlanden says a mutiny took place on Hudson's 1609 voyage, originating in quarrels between Dutch and English sailors. Van Meteran was the Dutch counsel in London when Hudson returned, and had access to Hudson's journals, charts and logbooks at the time.

1615

- The first Dutch settlement, Fort Nassau, was founded on Castle Island, near present-day Albany. The settlement served mostly for the fur trade with the natives. It was later replaced by Fort Oranje (or Fort Orange) at present-day Albany.

1625

- Juet's journal of the voyage was published in Purchas His Pilgrims. Portions of Hudson's journal of the voyage were published in John De Laet's history, Nieuwe Werelt.

Here's a contemporary article by Emanuel Van Meteren about the third voyage:

"We have observed in our last book that the Directors of the East India Company in Holland had sent out in March last, on purpose to seek a passage to China by northeast or northwest, a skilful English pilot, named Herry Hutson, in a Vlie boat, having a crew of eighteen or twenty men, partly English, partly Dutch, well provided.

"This Henry Hutson left the Texel on the 6th of April, 1609, doubled the Cape of Norway the 5th of May, and directed his course along the northern coasts towards Nova Zembia; but he there found the sea as full of ice as he had found it in the preceding year, so that they lost the hope of effecting anything during the season. This circumstance, and the cold, which some of his men, who had been in the East Indies, could not bear, caused quarrels among the crew, they being partly English, partly Dutch, upon which Captain Hutson laid before them two propositions. The first of these was to go to the coast of America, to the latitude of 40 degrees, moved thereto mostly by letters and maps which a certain Captain Smith had sent him from Virginia, and by which he indicated to him a sea leading into the western ocean, by the north of the southern English colony. Had this information been true (experience goes as yet to the contrary), it would have been of great advantage, as indicating a short way to India. The other proposition was to direct their search through Davis's Straits. This meeting with general approval, they sailed thitherward on the 14th of May, and arrived on the last day of May with a good wind at the Faroe Islands, where they stopped but twenty-four hours, to supply themselves with fresh water. After leaving these islands, they sailed on, till on the 18th of July they reached the coast of Nova Francia, under 44 degrees, where they were obliged to run in, in order to get a new foremast, having lost theirs. They found one, and set it up. They found this a good place for cod-fishing, as also for traffic in good skins and furs, which were to be got there at a very low price. But the crew behaved badly towards the people of the country, taking their property by force, out of which there arose quarrels among themselves. The English, fearing that between the two they would be outnumbered and worsted, were therefore afraid to pursue the matter further. So they left that place on the 26th of July, and kept out at sea till the 3d of August, when they came near the coast, in 42 degrees of latitude. Thence they sailed on, till on the 12th of August they again reached the shore, under 37 degrees 45'. Thence they sailed along the shore until they reached 40 degrees 45', where they found a good entrance, between two headlands, and entered on the 12th of September into as fine a river as can be found, wide and deep, with good anchoring ground on both sides.

'Their ship finally sailed up the river as far as 42 degrees 40'. But their boat went higher up. In the lower part of the river they found strong and warlike people; but in the upper part they found friendly and polite people, who had an abundance of provisions, skins, and furs, of martens and foxes, and many other commodities, as birds and fruit, even white and red grapes, and they traded amicably with the people. And of all the above- mentioned commodities they brought some home. When they had thus been about fifty leagues up the river, they returned on the 4th of October, and went again to sea. More could have been done if there had been good-will among the crew and if the want of some necessary provisions had not prevented it. While at sea, they held counsel together, but were of different opinions. The mate, a Dutchman, advised to winter in Newfoundland, and to search the northwestern passage of Davis throughout. This was opposed by Skipper Hutson. He was afraid of his mutinous crew, who had sometimes savagely threatened him; and he feared that during the cold season they would entirely consume their provisions, and would then be obliged to return, [with] many of the crew ill and sickly. Nobody, however, spoke of returning home to Holland, which circumstance made the captain still more suspicious. He proposed therefore to sail to Ireland, and winter there, which they all agreed to. At last they arrived at Dartmouth, in England, the 7th of November, whence they informed their employers, the Directors in Holland, of their voyage. They proposed to them to go out again for a search in the northwest, and that, besides the pay, and what they already had in the ship, fifteen hundred florins should be laid out for an additional supply of provisions. He [Hudson] also wanted six or seven of his crew exchanged for others, and their number raised to twenty. He would then sail from Dartmouth about the 1st of March, so as to be in the northwest towards the end of that month, and there to spend the whole of April and the first half of May in killing whales and other animals in the neighborhood of Panar Island, then to sail to the northwest, and there to pass the time till the middle of September, and then to return to Holland around the northeastern coast of Scotland. Thus this voyage ended.

"A long time elapsed, through contrary winds, before the Company could be informed of the arrival of the ship in England. Then they ordered the ship and crew to return as soon as possible. But, when this was about to be done, Skipper Herry Hutson and the other Englishmen of the ship were commanded by the government there not to leave [England], but to serve their own country. Many persons thought it strange that captains should thus be prevented from laying their accounts and reports before their employers, having been sent out for the benefit of navigation in general. This took place in January, [1610]; and it was thought probably that the English themselves would send ships to Virginia, to explore further the aforesaid river."

From Narratives of New Netherland, 1609-1664

(Original Narratives of Early American History),

ed by J. Franklin Jameson, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1909.

2009

-

The 400th anniversary of Hudson's landing in the New World is quickly approaching and many American communities are making plans to celebrate the quadricentennial.