Henry Hudson

1570(?) -1611(?)

This is a collection of data

about

the life and voyages of English

explorer, mariner and adventurer, Henry Hudson, with a chronology

and maps, as well as some

additional notes on his times,

contemporaries and his crew.

It was compiled from

numerous sources by Ian Chadwick,

between 1995 and 2006.

Last updated:

March 28, 2005

| Written &

researched by Ian Chadwick, Text & design copyright Ian Chadwick © 1992-2007 |

|

|

Web design, Net training, writing, editing, freelance columns, editorial commentary, research & data analysis. |

Note: Spelling in the 16th and 17th centuries was seldom consistent and often done by the sound of the word rather than by a specified rule. That could lead to wildly varied spellings, depending on where the writer came from. For example, Martin Frobisher, from Yorkshire, spelt "service" as "sarves" which would have been how he heard it. Often these variants extended to a person's own name. Frobisher signed himself as Frobiser, Frobissher and even Furbisher. Alternate spellings of names and places are given in parentheses. Consistency in spelling would not arrive until well into the 18th century.

Introduction to an Expansionist Age

Henry Hudson was born at a turning point in English history. England was in a tumultuous era, rapidly changing from a predominantly agrarian society to a mercantile and maritime power. Strife between religious factions tore the nation apart, and upset international alliances. Economies were changing, European wealth and trade shifting from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. It was a turbulent, rich and exciting era.

Henry VIII's break from the Catholic Church in 1534 had isolated England from most of Europe, and for most of the century threatened war to restore Catholic power - preferably through a subservient Catholic ruler on the throne.

Henry's main allies were a group of small, rebellious states in Northern Europe. The Netherlands were fighting to slough off Spain's domination, some of the German states were fighting to establish their Protestant church free of the Pope and Catholic control.

The Protestant Reformation had begun with Martin Luther in 1517 and spread rapidly among many nations. Calvinism became the official state religion of Scotland in 1560. Henry wasn't terribly sympathetic to the Protestants - he would have remained Catholic had the Pope been amenable to granting him a divorce. But the Pope didn't distinguish between the selfish source of Henry's quarrel and the argumentative Protestants like Luther and Calvin. So Henry VIII became the reluctant champion of the Protestant cause, despite his personal misgivings.

Henry was also not terribly interested in the New World, either, and was more intent on his own quest for an heir than in exploration. When Henry died in 1547, his sickly nine-year-old son, Edward, was placed on the throne. Edward's inheritance also included the debts left behind by Henry's uncontrolled spending.

Edward VI was the puppet of staunch -often radical - Protestant advisors. During his short time, the English economy further weakened, the continuing result of Henry's mismanagement. Money was devalued, products from the New World flooded English markets while demand for domestic products waned. The ambitious Earl of Warwick, John Dudley, controlled Edward's purse strings and virtually ruled England. He was undone by his attempts to place his family on the throne following Edward's death, through a forced marriage between Lady Jane Grey and his son.

Lady Jane was declared queen, but the people denied Dudley's ambitions and wouldn't support her. After nine days, Mary Tudor, Henry's eldest daughter and a staunch Catholic, rode into London on a wave of popular support. Lady Jane was imprisoned and executed. England briefly returned to Catholicism at the hands of "Bloody" Mary, whose short reign (1553-58) was marked by brutal repressions of Protestants. Those few, violent years served to push England firmly into the Protestant camp, and to push the treasury deeper into the red.

Elizabeth became the third woman on the English throne in a row, in an age still dominated

by male heads of state ("Woman in her greatest perfection was made to serve and obey man",

wrote John Knox, First Blast of the Trumpet against Monstrous Regiment of Women, 1558). She strove to to eliminate the religious unrest that had

marked her predecessors' rules. Unfortunately, the machinations of Mary Queen of Scots

and her Catholic faction threatened several assassination plots against

Elizabeth, forcing Elizabeth to take a stronger Protestant stance. She

executed Mary to stem the continual threats.

Elizabeth became the third woman on the English throne in a row, in an age still dominated

by male heads of state ("Woman in her greatest perfection was made to serve and obey man",

wrote John Knox, First Blast of the Trumpet against Monstrous Regiment of Women, 1558). She strove to to eliminate the religious unrest that had

marked her predecessors' rules. Unfortunately, the machinations of Mary Queen of Scots

and her Catholic faction threatened several assassination plots against

Elizabeth, forcing Elizabeth to take a stronger Protestant stance. She

executed Mary to stem the continual threats.

Elizabeth felt forced into war by the persecution of European Protestants by Spain and France. She sent an army to to aid the Huguenots (Calvinists who had settled in France) after more than 3,000 were massacred in France, in 1572. She also sent assistance to Protestant factions on the continent and in Scotland, and assisted the Netherlands in their bid to gain independence from Spain.

Philip II of Spain decided to end Elizabeth's interference by marrying her, but Elizabeth rejected his marriage proposal. That, combined with his outrage over continued English piracy and forays into Spain's New World colonies, was the final straw for Philip. The indignant Spanish King gathered his navy and sent a large Armada to raid England and bring Elizabeth to heel. However, the English won the naval battle and overnight England emerged as the world's strongest naval power, setting the stage for later English imperial designs.

It was also a time of spies. Philip II had his spies in England, and even in the court of Elizabeth. On the English side, Sir Francis Walsingham had created his own network of spies who sniffed out foreign intrigues and plots against Elizabeth. Double agents, disinformation and intrigue played a part in the activities of both countries.

The Catholic Church, reacting to the growing protestant movement, attempted to reform itself through the Council of Trent (1545-62) but its efforts failed to win back to the fold its Protestant critics. At the same time, the Council subordinated the church hierarchy to the rule of the Pope, and created a flurry of saints in an attempt to stiffen the weakening faith within its own supporters.

One of the advantages of the Protestant revolution was that Protestant monarchs gathered more power and financial control into their own hands than they had previously held. With such central authority, they were able to personally manage and direct overseas exploration without interference from the church or to subvert their goals to the church's agendas.

Since the voyage of Columbus, the competition to exploit the New World, and to gain advantages in the rich spice trade with the Orient had been frantic and aggressively pursued among most of the Western European nations.

Partly driving this hunt for new trade routes was the rapidly expanding Ottoman Empire, spreading from Turkey into Asia and Southeastern Europe. The empire had captured Constantinople in 1453; Turkish expansion reached its peak in the mid-16th century under Suleyman I (Suleyman the Magnificent). The Turks defeated the Hungarian army in 1526 and captured a large portion of Hungary. The Ottomans pushed deep into Persia and Arabia, Egypt, Syria and Algiers. Most of the Venetian and other Latin possessions in Greece also fell to the sultans. Mediterranean commerce was threatened by corsairs who sailed under Turkish auspices.

Suleyman also meddled in European politics. He allied with France, usually against Venice and the Holy Roman Empire, but he also supported Lutheran rebels in the Holy Roman Empire. He hoped by encouraging disunity in Christianity, he would decrease the chances of Christian Europe uniting in a Crusade against the Muslim Ottomans. Catholic forces were diverted from their war with the protestants to battle the expansionist Turks. Ottoman pressure may have played a decisive role in persuading the Habsburgs to grant concessions to the Protestants in the 16th century, thus encouraging the spread of Protestantism.

Having spread across the land trade routes, the Ottomans had settled down to control them and make a profit. Before they took control, trade caravans from the Orient had paid kings, warlords and bandits along their route so that the price of goods doubled, tripled - and even went to 50 or more times their original cost. Then the Ottomans added their "taxes" on top, putting great financial pressure on European merchants to find a less expensive way to get their goods. Along with the wars and the piracy in the Mediterranean region, the stranglehold on the land trade routes encouraged maritime nations of Europe to find a way around the Ottomans and restore some of the profits back to their own hands.

The base of mercantile power soon shifted from Venice and Genoa to the nations along the Atlantic where ships could roam freely without fear of Ottoman pirates. The Ottoman Empire was not pushed out of Europe until 1699, and in the meantime her economy decayed while overseas expansion enriched the West.

The New World had been discovered just over a century before Hudson enters recorded history. In the first half of that century, Spain and Portugal competed for control and trading dominance. The Portuguese proved capable and daring navigators, going to further reaches of the globe than anyone before them. They so challenged the larger and more militant Spanish that in 1493 and again in 1522 the Pope had to intervene and split the world into two realms of control, one for each nation.

Portugal, however, lost its lead when King Sebastian died in 1578. In 1580, tired of the factions vying for the throne in Lisbon, Philip II of Spain claimed to the vacant throne for himself and annexed Portugal. From 1580 to 1640, the two Iberian kingdoms were linked together under the Spanish crown. Phillip gained a navy, a treasury and a nation's colonies - but quickly discovered the efforts of maintaining its colonies and fleets had exhausted Portugal's financial resources. A century of war trying to retain control of the Netherlands cost Spain a fortune and forced her to dilute her forces over several fronts. By 1596, Philip II was formally bankrupt.

For most of the sixteenth century, Spain was the most powerful nation in Europe. Her armies conquered kingdom after kingdom in the New World, bringing untold riches into the Spanish coffers. Spanish colonies sprang up and Spanish merchants sailed unhindered around the world establishing lucrative trade routes in spices, materials and curiosities. Heavily-armed Spanish warships rules the oceans - but inexorably that was eroded: competition, war and the profligate spending of the Spanish monarchy soon took their toll.

Both Spain and France had recently consolidated their nations, uniting often warring kingdoms into the larger national entities, which opened new opportunities for commercial growth and capitalism.

France, although larger and richer than both England and the Netherlands, was initially less interested in this adventure than her neighbours. Unlike Spain's empire, "New France" produced no great sources of gold and silver even at its peak. The French traded for furs and fished off the coast of Newfoundland; New France was a loose population of trappers and missionaries, dotted with military forts and trading posts. Colonization was sporadic, and stifled by inconsistent policies and government interference. Although Jacques Cartier had tried to found a colony at Montreal, in 1536, the first successful French colony in the New World was Quebec, was not established until 1608, long after many other nations had done so. The French empire was slow to start, and failed to match the wealth of New Spain or the growth of the British colonies.

France and Spain were the bastions of the Catholic faith and a great part of their drive to colonize was done in concert with the Church's determination to convert the natives to Catholicism - by force where necessary. And in the process the native cultures were to be firmly but absolutely oppressed. Neither the British nor the Dutch were driven by this need to convert and thus "prove" the superiority of their faith, although Protestant missionaries were to arrive in greater numbers in the next century or two, but they were not driven by the same focus as the Catholics.

The other maritime nations of the West - the Netherlands and England in particular - didn't respect either the division of the world or the Catholic church's attempts to control things outside national borders. These nations wanted their share of the spoils. Both quickly sent explorers, whalers, fishing fleets and merchants to exploit the New World and to open trade routes. And along the way came inevitable clashes with the Spanish and Portuguese who claimed the waters and lands for themselves.

Despite the riches in the New World, most European nations were focused on trade with the Orient. The lure of spices, silks, gems and other luxury items was more compelling than mundane fish and furs that required more work to obtain. Worse, the New World was full of aggressive natives - "savages" - who fought with the Europeans and often won their battles. But geography was in the way. There were only two maritime trade routes to the Orient and the Spice Islands known: around the southern tip of Africa or the bottom of South America. Both voyages were long and dangerous. Pirates and privateers straddled both routes and could steal both cargo and the ships carrying it. Crews often got mutinous or sick on the long voyages. A long journey meant lower profits - more money was required to pay crews, ships needed more refits and repairs. A shorter passage through the north would both reduce the dangers and the time, as well as increase the profits. It was very attractive to the merchants who invested in the expeditions.

Europe's economy was rapidly changing in this period, nowhere more so than in England and Holland. The sudden increase in gold and silver caused both to become devalued: the more that arrived, the less valuable it became. The middle class of merchants was on the rise and land ceased to be the basis of wealth as trade propelled incomes. Bills of exchange began to replace cash as the staple of business transactions, and banks began to open in major cities. Businessmen combined their resources to become joint shareholders in large companies, rather than venture merely their own capital - a new concept for capitalism.

"A worthy merchant is the heir of adventure, whose hopes hang much upon the wind," wrote Nicholas Breton in The Good and the Badde (1616). "Upon a wooden horse he rides through the world, and in a merry gale he makes a path through the seas. He is the discoverer of countries and a finder out of commodities, resolute in his attempts, and royal in his expenses."

New plants introduced from the New World changed agrarian crop patterns - corn and potatoes in particular, but also beans, squash, tomatoes, pumpkins and peppers - which mean a drop in domestic crop prices and a shift in rural economies. Farmers could harvest a lot more food from their small plots if they planted corn or potatoes instead of the traditional wheat.

More exotic foods were also imported: sugar, coffee and cocoa. In addition, the harvest from new fishing grounds in the New World meant an increase in protein. These new foods meant more and better food for peasants, which meant better health and longer lives. Better health meant more people (the average life expectancy in England in 1600 was 48 years, up from an estimated 36 years a century earlier).

The Dutch had quickly commanded the business of shipping grain from the Baltic states into the rest of Europe, a lucrative trade that reached its peak in 1618.

The rapid population growth in the 16th century strained the English economy. Serious harvest failures in every decade of Elizabeth’s reign further weakened it. Prices for food and clothing skyrocketed in the last decade of Elizabeth's reign, a time known as "the Great Inflation." Starvation, epidemic disease, and roving bands of vagrants looking for work marked the 1590s.

Europe overall saw a population surge in the 16th-17th centuries. A lot of people moved from the farms and small towns to the cities, causing great swells in urban populations, changing the job market. Many of the new industries moved to the countryside to be closer to the source of workers.

England's population in 1500 was about 5 million. By 1700 it had almost doubled to 9 million, a faster rate than any of its neighbours. In the same period, Spain and Portugal grew from 9 to 10 million; the Low Countries from 2 to 3 million and France 16 to 19 million. Germany - a collection of independent and often warring states - grew from 13 to 15 million.

New raw materials - woods, minerals, metals - were improving European industrial processes. The sawmill was invented in the late 15th century, and sped the pace at which planks for ships and houses could be manufactured. There were other advances in mining and manufacturing techniques. Blast furnaces - invented in the early 15th century - were producing 60,000 tons of iron by the next century.

England grew rapidly in prosperity under Elizabeth I and her successor, James I. In 1597 England was described as, "The realm aboundeth in riches, as may be seen by the general excess of the people in purchasing, in buildings in meat drink, and feastings, and most notably in apparel." But like the rest of Europe, England was in a century of inflation: prices rose, rents rose, taxes and the cost of living rose steadily. In France, grain purchased in 1600 cost seven times what the same amount had cost in 1500.

To counter the loss of faith in the English economy, Elizabeth issued a new currency with a standard amount of precious metal. This not only raised confidence in the English currency, but it allowed businesses to enter into long-term financial contracts - quickly resulting in expanded overseas trade.

The Royal Exchange was founded in the 1560s to help merchants find secure markets for their goods, while merchant companies were chartered to seek new outlets for English products and establish new trading opportunities.

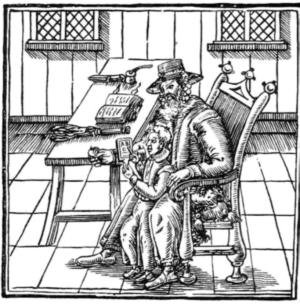

One of the main advances was in literacy and

education, in great part thanks to the invention of the printing press

in 1450 and its rapid spread. William Caxton set up the first press in England in 1476

and by Hudson's day printing was big business. Between 1560 and 1650, England experienced an unprecedented an age of school-building and educational endowment.

By 1650, 142 new schools had been founded and 293,000 pds. had been

donated to

fund grammar (secondary) school education.

One of the main advances was in literacy and

education, in great part thanks to the invention of the printing press

in 1450 and its rapid spread. William Caxton set up the first press in England in 1476

and by Hudson's day printing was big business. Between 1560 and 1650, England experienced an unprecedented an age of school-building and educational endowment.

By 1650, 142 new schools had been founded and 293,000 pds. had been

donated to

fund grammar (secondary) school education.

Oxford and Cambridge universities grew in size and importance, increasing from 800 students in 1560 to 1,200 by 1630. Cambridge started its own printing press in 1584 and Oxford in 1587. In 1604, the two universities were granted representation in Parliament, and both later sent leaders to the New World.

By 1640 nearly 100 percent of the gentry and merchants in England were literate and as much as 50 percent of the yeomanry. But only 10 percent of the husbandry class, and none of the peasants were able to read or write. Literacy was higher in the towns and cities than in the countryside. See search.eb.com/shakespeare/macro/5009/49.html. London, with its population of 200,000 by 1600, was estimated to be 60 percent literate. Overall, England was about one third literate (30 percent for men and 10 percent for women). In contrast, in France and Spain only an estimated one sixth of the population was literate.

As a result of this increased literacy among the general public, the latter half of Elizabeth's reign saw literature, plays and poetry flourish. There was an unbridled surge in creativity and the arts that continued past the reign of James I. Many of the works were romantic and dramatic, and many new literary techniques and styles were developed, including the first English novels. It was the age of the great playwrights, including Johnson, Marlowe and Shakespeare.

As a result of this growing literacy, books were widespread as publishing developed and grew in Elizabethan England. English people could read the exploits of other explorers and navigators, read the theories about the world and the passages over the north. It created a culture of excitement and adventure. In 1577, the Countess of Warwick commissioned English translations of the latest works on China, Japan and India. The Countess was preparing herself for what she another other investors felt was the certainly Martin Frobisher's latest attempt to find a passage to Cathay would succeed.

The period between the mid-sixteenth and mid-seventeenth centuries became known as the "Scientific Revolution." New ideas, new inventions and new technology swept Europe, especially in the areas of astronomy, mathematics, optics and physics. It was the century that saw Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, Bacon, Descartes and Pascal.

Two decades of war with Spain, plus a decade of war with Ireland, drained England's coffers. Queen Elizabeth was forced to sell roughly one-fourth of all crown lands to help pay for the burgeoning war debt of 4 million pds. She grew increasingly dependent on parliament for her income, which rose from an annual average of 35,000 pds. to more than 112,000 pds. a year by the time of her death.

The first two decades of the 17th century saw a rural and economic crisis. Harvests failed. More land was taken over by farming, but they were more than matched by a population increase that demanded more food. The shortages led to revolts in rural areas and even starvation. The rural economy did not fully recover until the middle of the century, long after Elizabeth had passed on. The nation that could barely feed itself in 1600 was exporting grain by 1700.

Spinning and weaving had traditionally provided employment for thousands of rural English families - upwards of 90 per cent of all English exports were broadcloth - "white cloth" - that went to the Low Countries and Germany for dyeing and finishing. That business reached its peak in 1550. In parallel with the harvest failures, the cloth trade suffered a collapse in the early part of the 17th century. When the Thirty Years' War (1618-48) began, trade routes became disrupted and new, cheaper sources of wool were sought by England's trading partners. Cloth exports had grown, but suffered stiff competition from finer Spanish products.

Worse, England lost its last hold on the continent in 1558, when Calais was recaptured by the French. English merchants had to find another port for their goods - Antwerp was the international marketplace they used until the Spanish captured and closed in in 1585. The decline and closing of the port of Antwerp again forced English merchants to seek other centres to sell their goods, going this time to Amsterdam.

The English mercantile economy struggled to transform itself from a single-commodity economy based almost solely on cloth exports, to a diversified one, offering dozens of domestic and colonial products for both internal and external sale.

Elizabeth's personal financial woes combined with the volatile nature of the English economy to create a swell of mercantile pressure that demanded new markets, new goods for trade and new sources of income. She was slow to encourage the voyages of discovery that would soon lead to England's dominance in the world of trade and empire. She was even partner in some of the ventures, and approved charters to allow English merchant combines to have monopolies on trade in specific areas. Elizabeth preferred to encourage the privateers who raided the shipping and ports of other nations.

Although the first English expedition to the New World - John Cabot - was sponsored in 1497 by Henry VII, the English showed little interest in exploration until Elizabeth arrived. In 1560, English merchants enlisted Martin Frobisher to search for a Northwest passage to India (and later set him up to mine gold he had discovered on Meta Incognita - but what he found onshore proved to be only pyrite). Frobisher was particularly determined to find a Northwest Passage, and owned both maps and a globe (a rarity in that time) showing a definite passage to Asia through the north.

Between 1576 and 1578 Frobisher and John Davis (Davys) explored the Atlantic coast searching for the passage. Queen Elizabeth also granted charters to Sir Humphrey Gilbert and Sir Walter Raleigh to colonize America. By the seventeenth century, the English had taken the lead in colonizing North America, establishing settlements all along the Atlantic coast and in the West Indies.

Beset with financial problems, faced with a rapidly changing economy, and trying to establish her nation in the forefront of maritime powers amongst a lot of competition, Elizabeth managed her balancing act for 45 years. She encouraged a series of trading companies and their explorations, right until her death. But for all her attempts and her parsimonious reluctance to spend her money, Elizabeth still left the Crown more deeply in debt than it was when she was placed on the throne.

Her successor, James I, continued to support these mercantile ventures, and also promoted the establishment of colonies in the New World. By the time James took the throne, the balance of power had shifted dramatically in Europe. The alliance between the Netherlands and England was giving way to competition and even suspicion. Spain's dominance was waning rapidly and France was becoming a serious contender in the trade wars. The Ottoman Empire was also stagnating and its economy weakened from decades of war and dwindling revenue from its overland trade routes.

James wanted peace and discouraged the piracy and lawlessness that Elizabeth had allowed (he imprisoned Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower for 12 years). However, he proved even less capable of handling the fragile economy than Elizabeth, and wildly overspent his own income. James was far too generous with his favourites, was prickly and bristled under the tight controls Parliament tried to place on his spending. James inherited from Elizabeth a debt of 400,000 pds. By 1606, it had risen to 600,000 and 900,000 by 1618.

In his attempt to find more money, James raised duties, which further hurt the economy. A failed attempt to bring in widespread taxation forced James to sell titles for cash and raise rents on crown lands, neither of which proved popular. Parliament and James were soon to be at loggerheads over money.

It was in this turbulent atmosphere that Henry Hudson first set sail.

Contemporary history - 1498 to 1607:

- 1498: John Cabot, under the English flag, sailed with five ships to the North American coast. Cabot died on that voyage.

- 1519-22: Magellan circumnavigated the world. He discovered and claimed the Moluccas in 1519.

- 1521: Henry VIII asks London merchants to finance a company to pursue overseas ventures, but the merchants feared this would hurt their existing trade with Portugal and Spain, so they decline.

- 1521: Ferdinand Magellan discovers the islands he would name the Philippines, after Philip II of Spain. Magellan was slain later this year when he attempted to intervene in a dispute between native chieftains.

- 1524: Verazzano explores the eastern cost of America from 34 to 50 degrees north, entering what is now New York Bay.

- 1546: The Mary Rose, Henry VIII's grand, massive and expensive warship was launched in July. The only existing illustration of her shows a 4-masted barque, about 600 tons, with two castles (bow and stern). There are 90 guns in several rows along sides, the lower set lying close to the water level. On that calm July morning, the Mary Rose sailed out of Portsmouth harbour into the Isle of Wight sound to do battle. She turned to starboard to present her broadside guns, heeled over and sank very suddenly in 40 fee of water without a shot fired.

- 1547: Henry VIII died.

- By 1550, the Portuguese had established control over the sea routes to and in the Indian Ocean. They had found the source of the oriental spice trade, and established relations with China and Japan. The Portuguese spread their influence throughout the region with amazing rapidity and their dominance in trade continued until the late sixteenth century.

- 1552: London merchants finally realize the trade opportunities they're missing and form a joint-stock company with 200 shareholders. They call themselves "The Merchants Adventurers of England for the Discovery of Lands, Territories, Isles, Dominions, and Seignories." This would later become changed to the Muscovy Company.

- 1553: John Cabot's son, Sebastian, was made governor of the "Company of Merchant Adventurers" in London, and directed English trade missions to Muscovy until his death (1557?). He was commissioned to find a Northwest Passage over Russia, but was unsuccessful. Cabot not only believed there was a sea route north of Russia, but that it had been used by sailors in ancient times. Sebastian claimed to have accompanied his father on John's first voyage to North America, 1497, and that he had sailed on another expedition, in 1508, to the North American mainland, visiting Labrador and Hudson Bay (from 50 degrees north to the mouth of what is now Hudson's Strait). Later historians would question Cabot's claims.

- 1553: Hugh Willoughby sets out in May to the Kara Sea, to find a route to Cathay (China). He sighted a land he called 'Gooseland' (Novaya Zemlya). Sebastian Cabot provided advice and information to Willoughby for this journey.

- 1554: Willoughby and his crew of 70 perished when wintering over, after discovering the islands called Novaya Zemlya (Nova Zembla). His second-in-command, Richard Chancellor and Stephen Borough, travelling in the Edward Bonaventure, were separated from Willoughby. They managed to reach the White Sea, and land near what is present-day Archangelsk. Chancellor travelled south overland to Moscow at the invitation of Ivan IV. His negotiations with the Tsar opened avenues for trade with Russia and the Company of Merchant Adventurers renamed itself the Muscovy Company.

- 1555: The Muscovy Company is formed to trade with Russia.

- 1556-1557: Stephen Burrough tried the same northeastern passage as Willoughby but returns convinced there is no way to break through the ice barrier and reach China that way. He landed on 'Gooseland.' Sebastian Cabot helped equip Burroughs.

- 1558: Queen Elizabeth I comes to the throne the same year England

lost Calais, its last hold on the continent.

Portuguese explorers may have sailed into today's Hudson Bay (and again in

1569).

Portuguese explorers may have sailed into today's Hudson Bay (and again in

1569). - 1561: Cartographer Giacomo Gastaldi published a map showing North America and Asia separated by the Strait of Anian. This would lead subsequent explorers to believe an ice-free opening existed across the north. By 1564 the "strait" was appearing on other cartographers' maps.

- 1562: John Hawkins, the first English merchant trader, took three ships from London to Sierra Leone in West Africa and kidnapped 300 Africans 'by the sword, and partly by other means'. Hawkins then crossed the Atlantic and sold the Africans into slavery at Hispaniola (Haiti). He returned to England with ginger, sugar, pearls and hides, which he sold to London merchants. Hawkins made a second slaving expedition in 1564-65. Elizabeth I lent Hawkins a royal ship for that voyage, and Hawkins was backed by a group of wealthy London merchants and noblemen. He made a third voyage in 1567-68.

- 1564: Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius added the Strait of Anian in his new map of the world, as well as showing a straight passage over the top of North America.

- 1565: Spanish ships sailing from Mexico's west coast reach the Philippine islands and then return with merchandise a few months later, establishing a trade route between the two.

- 1566: The revolt of the Netherlands began. Sir Humphrey Gilbert publishes A Discourse of a Discoverie for a New Passage to Cathaia, which includes a copy of the Ortelius map showing a Northwest Passage. Gilbert's peition for support from Queen Elizabeth to allow an expedition was foiled by the Muscovy Company, which claimed it had the monopoly on all northern expeditions.

- 1568: The Wars of the Dutch Secession began, lasting to 1648. Also called the Eighty Year's War and the Dutch Revolt, it was the start of the independence of the Netherlands from their Spain overlords.

- 1569: Gerhardus Mercator, influential map maker, published his map. Based on mathematical principles, it is a flat map using the projection that still carries his name today.

- 1571: The Spanish found the city of Manila in the Philippine Islands.

- 1573: Queen Elizabeth appointed Sir Francis Walsingham as secretary of state for foreign affairs. Walsingham replaced the more conciliatory William Cecil (Lord Burghley). Walsingham was more aggressive towards England's enemies and much more supportive of voyages of exploration (and piracy) to gain England a greater advantage in trade.

- 1576:

Sir Humphrey Gilbert, a favourite of the Queen,

publishes

Discourse to prove a passage by the northwest to Cathay and the East

Indies. His ideas get the Queen's support. She got the court to back

Martin Frobisher's first voyage (financed by Michael Lok). Frobisher reached Baffin Island, and

returned with a sample of ore that Michael Lok would be led to believe by an

Italian alchemist contained gold. Lok immediately started negotiations with

Queen Elizabeth for a second expedition to mine the ore.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert, a favourite of the Queen,

publishes

Discourse to prove a passage by the northwest to Cathay and the East

Indies. His ideas get the Queen's support. She got the court to back

Martin Frobisher's first voyage (financed by Michael Lok). Frobisher reached Baffin Island, and

returned with a sample of ore that Michael Lok would be led to believe by an

Italian alchemist contained gold. Lok immediately started negotiations with

Queen Elizabeth for a second expedition to mine the ore. - 1577-78: Frobisher made two trips to gather his "gold" but it turned out to be worthless hornblende. In 1577 he entered what is now known as Hudson's Strait. His last voyage had 15 ships and 400 men, and in the end proved a financial disaster for everyone who invested. Queen Elizabeth herself invested 500 pds. in the venture, and loaned Frobisher her naval ship, the Ayd. Creditors would hound Michael Lok until at least 1615. English interest in a Northwest Passage also waned, following the debacle, but was later revived.

- 1578: The young Portuguese King Sebastian was killed during his African crusade, leaving the Portuguese throne vacant, an irresistible opportunity for Sebastian's uncle, King Philip II of Spain. By this time, Portuguese resources had been exhausted by the strain of trying to maintain both a domestic and a colonial economy.

- 1579: English adventurer Francis Drake, sailing in the Golden Hind, attempted to find the "Strait of Anian" in the North Pacific, and to reach the Atlantic via the north, thus bypassing the territory under Spanish control. He sailed up the coast near the mouth of the Rogue River, but abandoned his search because of rough weather and cold.

- 1580: William Bourne publishes his book, A Regiment for the Sea, urging exploration of polar routes to the east. Sir Francis Drake circumnavigates the Globe.

- 1580: Philip II of Spain annexed Portugal, whose throne had been vacant since his nephew's death two years earlier. This gave Philip a new Atlantic seaboard, a fleet to help protect it, and increased his empire from Africa to Brazil, and from Calicut (Calcutta) to the Moluccas (Spice Islands). Portugal remained a province of the Spanish Empire until 1640 but its dominance over the Eastern trade was already lost to the English and Dutch by 1600. Dr. Dee ships his interest from a Northwest to a Northeast Passage.

- 1581: Elizabeth knighted Francis Drake. Don Antonio, pretender to the throne of Portugal arrived in England in June, trying to raise a fleet to protect the Azores from the Spanish. Some of the inhabitants in the former Portuguese colony had refused to swear allegiance to King Philip. Although a fleet of 25 ships was assembled, Philip warned that if it sailed, it would mean a declaration of war by England, so the project was abandoned.

- 1582: Richard Hakluyt, 30, publishes his first book, Diverse

Voyages Touching the Discovery of America.

- 1583: Edmund Fenton of the Muscovy Company visited the Moluccas and the Spice Islands (the Dutch were there before the English). Fenton had the backing of the first Earl of Leicester (Sir Philip Sydney) and Secretary of State, William Cecil (Lord Burghley).

- 1584: Ivan IV - "The Terrible" - dies in Muscovy.

- 1585-88: John Davis (Davys) makes three voyages to the northwest. He charted the strait between Greenland and Canada and explored the eastern shore of Baffin Island. In 1587 he explored Davis Strait to Sanderson's Hope and reached the most northerly point reported by any European to that date: 72°45'N. He passes the entrance to a great, swirling, roaring strait, which he dubbed the "Furious Overfall," now called Hudson Strait. Davis reported a "great sea, free, large, very salty, blue and of unsearchable depth" when his ship was anchored off Greenland. He estimated it to be 40 leagues (120 miles) wide and believes the "passage is most probable, the execution easy." Henry Hudson may have served as mate with Davis on at least one (1587) of his voyages.

- 1585: Elizabeth sends an army of 5-6,000 soldiers and 1,000 horses to Holland to support the Protestant Dutch in their war for independence from the Catholic Spanish. The English were to stay in the Netherlands assisting the Dutch until 1604.

- 1586: Sir Francis Drake returned from Virginia with several colonists who brought with them pipes and the practice of "drinking" tobacco smoke (inhaling and apparently swallowing it). Smoking quickly developed as a popular, social pastime - the first smokers were called "tobacconists."

- 1588: Spanish king Philip II sends the Armada against England, but it is defeated. As an experienced mariner, Hudson would have probably served aboard an English ship in this battle, unless he was elsewhere.

- 1589: French King Henri III was assassinated. Henry Navare, a Bourbon, took the French throne, ruling as Henry IV.

- 1592: Sir John Burrough captures an East Indian carrack laden with 900 tons of spices, cloth and treasures from the orient. This excites more English adventurers to seek ways to get to these riches. The Levant Company is also created and becomes the fifth English company permitted to trade with Turkey. This year, too, the plague struck London, killing an estimated 10 per cent of the population.

- 1592: The Nine Years' War breaks out when the Irish revolt against their English overlords.

- 1595: Four Dutch ships under the command of Cornelius de Houtman reach Java by way of the Cape of Good Hope. The Dutch begin exploration of the East Indies.

- 1596:

Dutch explorers Willem Barents (Barentsz, one of

Peter Plancius' proteges) and Jacob Heemskerck discover the Spitzbergen

Islands, they touched northwest tip of Spitzbergen, 79°49' N . Barents

sailed east to Novaya Zemlya where his ship got locked in the ice. The crew

was forced to winter over for eight months in a cabin they built ashore (The

Saved House). They become the first European expedition to survive an

Arctic winter. In 1871, Norwegian harpooner Elling Carlsen, in pursuit of a

pack of walrus, discovered the ruin of The Saved House where Barents' crew

stayed. Archeological excavation works began in 1993 and proceeded in 1995.

Dutch explorers Willem Barents (Barentsz, one of

Peter Plancius' proteges) and Jacob Heemskerck discover the Spitzbergen

Islands, they touched northwest tip of Spitzbergen, 79°49' N . Barents

sailed east to Novaya Zemlya where his ship got locked in the ice. The crew

was forced to winter over for eight months in a cabin they built ashore (The

Saved House). They become the first European expedition to survive an

Arctic winter. In 1871, Norwegian harpooner Elling Carlsen, in pursuit of a

pack of walrus, discovered the ruin of The Saved House where Barents' crew

stayed. Archeological excavation works began in 1993 and proceeded in 1995. - 1596: Francis Drake died of dysentery off the coast of Panama. Two more Spanish Armadas, in 1596 and 97, are wrecked before they can threaten England.

- 1597: In June, Barents dies of scurvy on Novaya Zemlya after surviving the winter there. Heemskerck manages to sail the ship back to port.

- 1597: Dutch merchant Cornelius Houtman's returned froma disastrous voyage to the East Indies, yet the surviving ships returned loaded with valuable spices and a treaty with a sultan in Java.

- 1598: Don Juan de Onate claims all of New Mexico for Spain.

- 1598: Financial pressures caused Philip of Spain to secede the southern Netherlands to Archduke Albert of Austria.

- 1598: Philip III took the throne of Spain as the nation's power and wealth were in decline.

- 1598: Fedor ascends to the Muscovy throne, beginning the 15 years of the "Time of Troubles," a series of internecine fights and short-lived monarchs, that would end in 1613 when Michael Romanov claimed the throne.

- 1598: Dutch traders visited what they called "New Netherland, between the English colony of Virginia and New England, roughly from the South (Delaware) river, lying in 34-1/2 degrees to Cape Malabar, in the latitude of 41-1/2 degrees. Members of the Greenland Company made visits, but did not establish any fixed settlements, only shelters for the winter and two forts against the attacks of the Indians.

-

1599: The Dutch merchants who basically ran the international spice trade demanded London's merchants pay six and then eight shillings (40p) for a pound for pepper - previously sold for three shillings (15p) per pound. The London merchants would not tolerate the inflationary jump in prices. Since the London traders had grown in power and wealth of late, they decided to challenge the Dutch monopoly on the spice trade. A meeting was held in London in September, 1599, to discuss the increase. From that meeting, the English formed the English East Company, an association for the purpose of trading directly with India. Queen Elizabeth supported the merchants by sending Sir John Mildenhall to the Great Moghal to apply for trading privileges for English traders. The other principal English trading companies were the Muscovy Company, trading in northerly waters, and overland to Moscow; and the Levant Company, trading with Turkey and the Levant.

- 1598-1600: Richard Hakluyt published his 12-volume series on the explorations of English seafarers, The Principal Navigations. It includes accounts of the voyages of Frobisher, Davis and Willoughby. Hudson most likely read it and was influenced by the stories.

- 1600-02: English East India Company formed, with more than 200 subscribers (investors) raising almost 70,000 pds. The EEIC was given a monopoly on all English trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. It made at least 100 per cent profit on each of its first 12 voyages. It grew wealthy and strong as it fought the Dutch in eastern waters. The EEIC held their trade monopoly for many years and was virtually the sovereign British power in India for more than 250 years. The success of the EEIC worried the merchants of Amsterdam so much they clamored for a similar Dutch organization. In 1600, the States General of the United Netherlands agreed the future of the Dutch in the East should be protected by the establishment of a company along the English plan. So in 1602, the Dutch East India Company was chartered, with almost absolute powers of sovereignty and a monopoly of trade for the next 21 years.

- 1601: The East India Company sent a convoy under Sir James Lancaster to Sumatra in 1601 under James Lancaster. By the time the ships returned in 1603, the plague in London had killed 38,000 and Elizabeth was dead (not of the plague). Spain sent 4,000 troops to Ireland to help the Irish rebellion against the English, but they were defeated in the Battle of Kinsale.

- 1602: Captain George Weymouth (Waymouth) leaves England in Discovery (to be under Hudson's command in 1610) for the New World, to look for a northwestern route to the Orient. He sailed 100 leagues into the Furious Overfall (Hudson's Strait) before ice pushed him back. His journal of the voyage was not published until 1625, although Hudson may have known of his exploits and read his logs before he left for his own voyage to that area.

- 1602: Another explorer, Bartholomew Gosnold, left England, on March 26, with a crew of 32, to explore the New World. He named Cape Cod. His journals and logs were also available to Hudson.

- 1602: The Dutch founded the city of Batavia in Java, reviving the ancient name of Holland in the tropics. The site they chose for their city was a swamp. Batavia became the head-quarters of the Dutch East India Company and the headquarters of the Dutch colonial empire. In 1603, the Dutch blockaded, but never captured, the city of Goa, then a Portuguese trading port.

- 1603: Elizabeth I died. James VI of Scotland succeeded Elizabeth, becoming James I of England. England's war with Spain ended and England turned its energies to more exploration and trade.

- 1604: John Davis was killed by pirates off the coast of Sumatra. British soldiers leave the Netherlands. A second East India Company expedition under Henry Middleton arrived in Java at the end of 1604, and sent back a shipload of pepper. Middleton then proceeded to the Spice Islands and managed to get two ships back to England in 1606. Dr. John Dee Dee petitioned James I for protection against the accusation he was a wizard.

- 1605: John Cunningham, James Hall and John Knight, in three ships, explored the west coast of Greenland for Christian IV, of Denmark. A French trading post was established at Port Royal (Annapolis), Nova Scotia by Samuel de Champlain and the sieur de Poutrincourt. Weymouth explores the New England coast to find a place where English Catholics (unwanted in Protestant England) could found a settlement. Hudson may have used Weymouth's logs of this voyage and charts for his own 1609 voyage.

- 1605: John Davis was killed by Japanese pirates near Singapore.

- 1605: The Dutch East India Company sent out its third fleet to the East. The second of these fleets had established forts and factories in Malabar, and had established friendly relations with the princes of Sumatra. The third captured Amboyna from the Spaniards, and secured the whole town and island for the Company. By 1605, most Portuguese traders were driven from the Spice Islands by the Dutch.

- 1605: Annapolis Royal, in Nova Scotia, became the first permanent English-speaking settlement in North America.

- 1606: John Knight, in the Hopewell (Hudson's ship on his first two voyages), searched for the Northwest Passage along the coast of Labrador. James Hall, with five ships, is sent by Christian IV of Denmark to Greenland to Conduct mineralogical explorations. The first charter is granted to the Virginia Company, named after the 'Virgin Queen' Elizabeth I. Pero Fernandes de Queiros discovers the New Hebrides Islands. Willem Janzoon discovers Australia. Luis Van Torres explores the coastline of New Guinea. Francis Bacon was appointed Solicitor-General by James I.

- 1607: On May 13, 104 male settlers arrived at James City to found the second permanent English settlement in the New World. The EEIC established a trading post at Surat, on the west coast of India.